November 18, 2021 – NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Environmental Management Branch (EMB) biologist Jeffrey Collins presented the KSC Indian River Lagoon (IRL) Health Initiative Plan to the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program Management Board on November 16, 2021.

KSC IRL Health Initiative Plan Presentation Video

Video Link: NASA KSC EMB IRL Health Initiative Plan Presentation Video

IRL Health Initiative Plan Video Transcription

Hey I am Jeff Collins with NASA Environmental Management Branch and we are happy to be here today to talk about the NASA Indian River Lagoon Health Initiative Plan.

Duane, I am very happy that you could finally be here. I say we because I have some people here with me, or maybe I am with them, starting with Laura Aguiar, Nick Murdoch, Chief of Environmental Management Branch, and Don Dankert, Team Lead of our Environmental Planning group within the Environmental Management Branch.

So anytime, we have a break or after the meeting you can hit us up with questions or if you have questions about things that are going on.

I am especially excited to be presenting because in 17 years with the Corps of Engineers I was always the most hated person in the room. And I might be overstating, typically some people where probably ambivalent, but that is a tough job, so hopefully we can do better than that today.

And so, we are going to talk about the lagoon plan and its a brief presentation and then we are going to look at some funding and kind of talk about how NASA is structured so you can kind of have the full set of information to go with the plan.

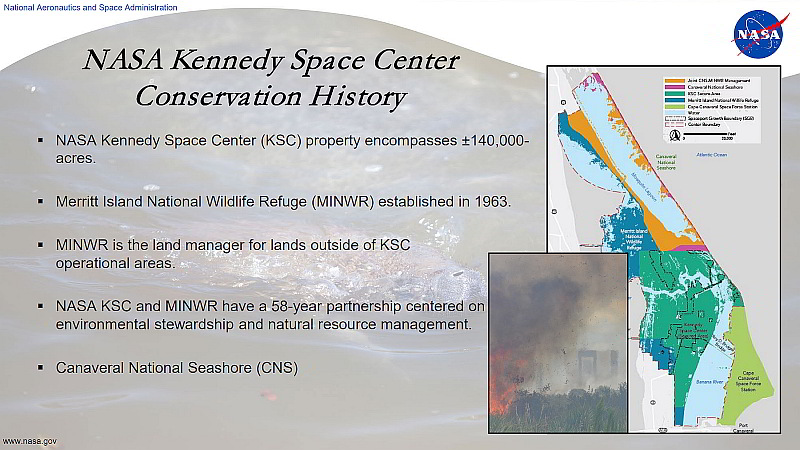

I think I have mentioned this to a few people the irony is never lost on me, the fact that Kennedy Space Center had some pretty significant environmental impacts when it was constructed, anybody can go online and figure that out. I think for the crawlerway and pad 39a, I think its about 350 acres of fill in the lagoon. You know, that’s what they did back in the late 50s and early 60s.

But out of that arose the 135,000 acre Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge. MINWR (minwar) as we call them, cause that’s a lot to say, so if I can say MINWR you will know what I am talking about. And, we have been working with them a long time and we coordinate with them pretty much on a daily basis. They are our land manager and they manage all areas outside of operational areas of Kennedy Space Center.

Not to short change Canaveral National Seashore. CNS. We work with them too, they just don’t manage quite as much adjacent to our operational areas. Both of those agencies kind of have their own things they are doing for the lagoon as well, but we collaborate on a lot of activities.

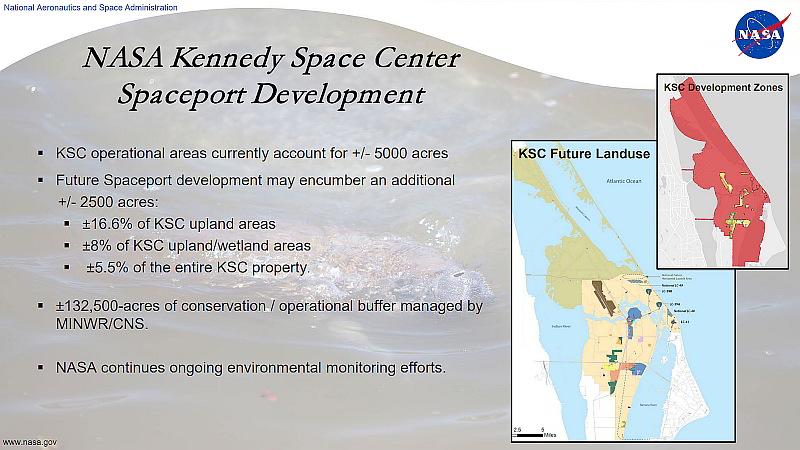

Things to come. Right now, we have about 5,000 about acres in operational areas. Based on the 2015 Master Plan, that will expand to about 7,500 acres of development with what we call the multi-user spaceport.

That sounds like a lot, but if you break it down its about 16.5% of the Kennedy Space Center upland areas, about 8% of the uplands and wetlands, or about 5.5% of the overall 140,000 acre boundary. So at the end of the day we still have about 132,000 acres of conservation. So it is a good deal especially considering the way the rest of the watershed was built out early on, through stormwater.

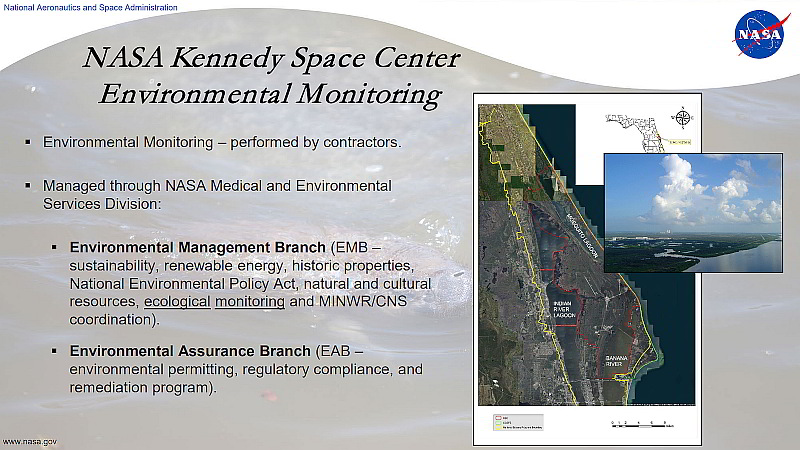

We have done environmental monitoring out there for a long time and we continue those efforts. It really occurs in three main areas that guides the environmental monitoring, regulatory compliance, operations, and stakeholders support. We do a lot of work that benefits stakeholders, with our two primary stakeholders here being MINWR and CNS.

Looking at environmental monitoring, all this work is performed by contractors and the way we are structured, is the Environmental Management Branch manages a portion of that and the Environmental Assurance Branch, EAB, manages a portion of that

EMB, you can see the list there, its really a pretty eclectic list for one group. Sustainability, Energy, Historic and Cultural Resources, NEPA, Ecological Monitoring. And I highlight ecological monitoring cause that’s really the work we have done in the past where ecological monitoring is kind of the backbone of the Indian River Lagoon Plan.

And then the Environmental Assurance Branch, they deal with what I call the hard environmental, the Environmental Permitting, Regulatory Compliance, and Remediation. and they manage water quality issues, so they are part of the plan as well.

So going back to 1983 and burrowing down into the ecological monitoring, we started ecological monitoring which culminated with end of shuttle, with what Don likes to call the End of Shuttle Report.

That was in 2014, I don’t think you can read those names, but you no doubt know a lot of those people or have worked with those people. And many of you went to school together, a few people, NASA paid for people to get Phd.s

So that went on a long time, so now all that work, ecological monitoring is conducted under what we affectionately call NEMCON. Again, like Corps of Engineers, NASA has a lot of acronyms, just because you need them.

So the history of monitoring, I don’t have a full suite of monitoring up there, but there is a lot of biological monitoring, carbon sequestration, different things that NASA has monitored over the years, and is still monitoring most of that.

So an example of regulatory compliance, the Florida Scrub-jay, there is biological opinion, you know, compliance issues. We monitor for that. You have heard of Dave (???) before, he does a lot of that work along with others.

That would also be a stakeholder driven monitoring as well because we deal with MINWR as they prescribe burn and we deal with scrub-jays.

Launch impacts, obviously operational issues, and again stakeholders. Maybe, scrub vegetation, we pass on some scrub information to MINWR regarding scrub and how it is responding to fires. And they can hopefully use that to their benefit.

So moving on, kind of getting into the plan now, I credit Don, he won’t want credit, but I credit him with the idea of the lagoon plan. Over two years ago, talking to some people, they decided they need to move forward with that. So Don started that and I actually came on to NASA and took it up with the contractor and we actually put the plan together.

It is really needed, I give NASA credit for putting this together. You know, NASA really is a special place with the refuge and the property on three different bodies of water that comprise the Indian River Lagoon. And being on a barrier island.

What we proposed when we embarked on this really are what I call “actionable projects”. Projects that we could actually implement and not bite off too much.

There are projects such as putting culverts under the crawlerway, that if we went down that road, we would still be talking about that, and we wouldn’t have an IRL Plan, a Lagoon Plan. So we stayed away from those big ticket items.

Funding, always an issue, the ecological monitoring funded under NEMCOM is, you know, we have funding for a lot of those activities, some of the other items where we have to do studies and design and construction, we have to go find that funding. And we’ve got people that do that.

Looking at the various actions, whether its monitoring, restoration or collaboration, it is all geared towards informing management of the center, whether it be operational areas or areas outside the operational buffer, maybe even further than that, a little more regionally potentially.

And so, I call the plan a living document. If you don’t like that, I mean look at it this way, it is not a static document. We don’t know everything that needs to be in the plan. There are some studies proposed, that will get more information, and as we get that information we will put additional either studies or design construction elements into the plan.

For example, I know one area right now, that we could pull down a buffer, and talking with MINWR, improve circulation in the northern Banana River lagoon. So something like that that we have identified since the plan was written, then we will pull that stuff in. And certainly as the public has input and stakeholders, there might be additional things that go in there.

And we did coordinate with stakeholders very early on, with the beginnings of the plan in terms of MINWR, CNS, Space Force, and Fish and Wildlife Commission. They all had input early on into this Plan.

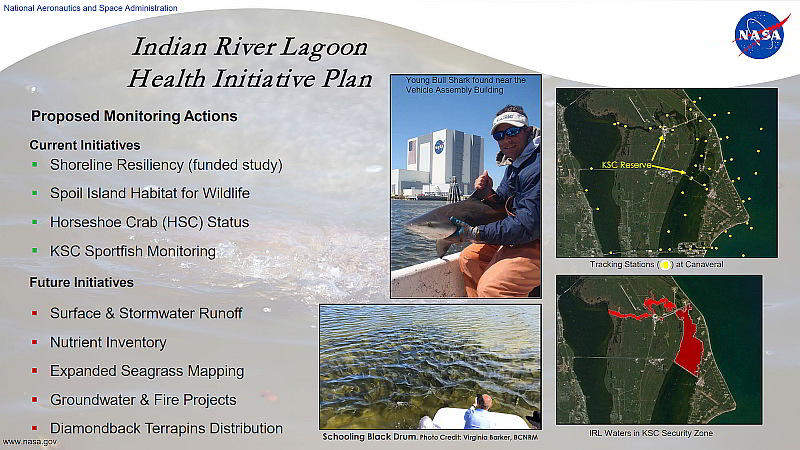

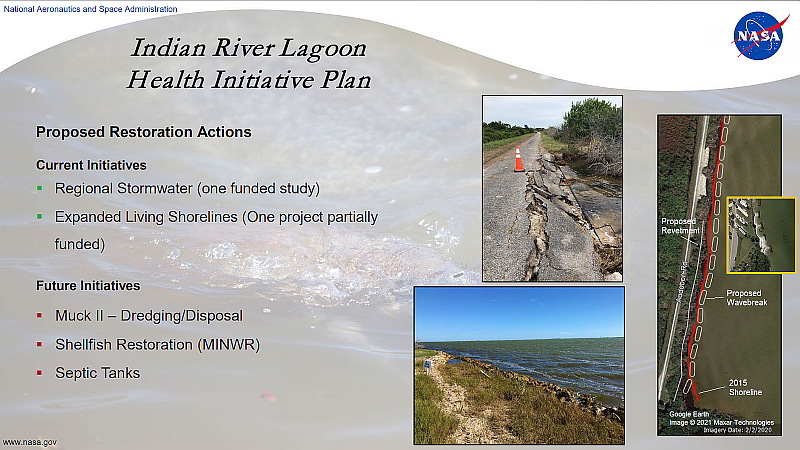

So, getting down into the details of this plan, items in green are items that are funded, items in red are not funded. We are looking for funding.

And so proposed monitoring actions: Shoreline Resiliency is a big thing for NASA. Over the last twenty years the mean water level has come up about a half of a foot. That is significant, not only for the dune that protects pads 39B and B but also for the lagoon. And that has implications for lagoon not just NASA. And you will see some pictures on that in a minute.

It is not cheap, we spent 26 million dollars over the last 5 or 6 years maintaining three and a half miles of dune. So there’s significant dollars that go into some of these projects.

Spoil Islands. We’ve got a lot of spoil islands up in the Mosquito Lagoon. Again, ironic, historically they were impacts now they are a benefit to horseshoe crabs, shorebirds whether they are foraging or nesting potentially. It all depends what’s on the spoil islands. So we are going to take a look at that and see if there could be benefits provided to the lagoon by doing some work on those.

Horseshoe Crabs. Fairly important. Again that intersects with shoreline resiliency. As we lose shoreline we need to protect infrastructure. We don’t want to be dumping a bunch of rocks on to the shoreline if we have key spawning areas for the horseshoe crab, so we are going to take a look at that. And that’s funded.

Sport Fish Monitoring. This is some of the best work.

Did Doug Scheidt make it in here today? He is not here? Well, he has the second best job in the world. Eric Reyier has the best job in the world, dealing with sport fish monitoring and what we call the FACT array or the FACT Network. That’s the Florida Atlantic Coastal Telemetry Network.

It is a series of acoustic receivers out in the Atlantic, and in this case the Indian River Lagoon, and you put a acoustic tag in fish and they swim around and you learn information about their daily, seasonal and spawning movements.

In this case, with the receivers we have, and this is published work I think I provided to Kathy and Virginia Barker, we had these NASA secure areas, nobody fishes in those areas except occasionally Eric Reyier will hook and line fish to put tags in them because you can’t harpoon them, don’t want to snag them, so you have to catch them on hook and line.

And what we found is that secured area is very important to the lagoon in terms of protecting large brood fish. They spend a lot of time in there and then they immigrate out of those areas to spawn to help repopulate the rest of the lagoon with fish. So, hugely important.

Some of the important future initiatives: Surface water runoff, nutrient inventory, things like that, they’re not funded currently. We are looking for funding for that. And that is some of the meat of the plan, anything to do with water quality is hugely important.

No seagrass to map.

Groundwater and fire projects. That’s interesting to me because I know in some places work has been done looking at fire and groundwater relationships, they’ve seen increased phosphate in the groundwater.

MINWR does a lot of prescribed burning because of all they scrub-jay families we have at the center. So we thought we might take a look at that if we could, if funding is available.

Or we might just monitor the ditch outfalls and see what the nutrient levels are and deal with that.

Diamondback terrapin is another opportunity for monitoring there.

You see a big school of Black drum there that we saw a couple of weeks ago, that’s up in that secured area. Right up here.

One last thing to point out is the turning basin, right by the VAB building, is a nursery ground for pup bull sharks. Small bull sharks go in there, and they grow up, and then leave. So, that’s some interesting information we wouldn’t know if we weren’t doing this kind of monitoring.

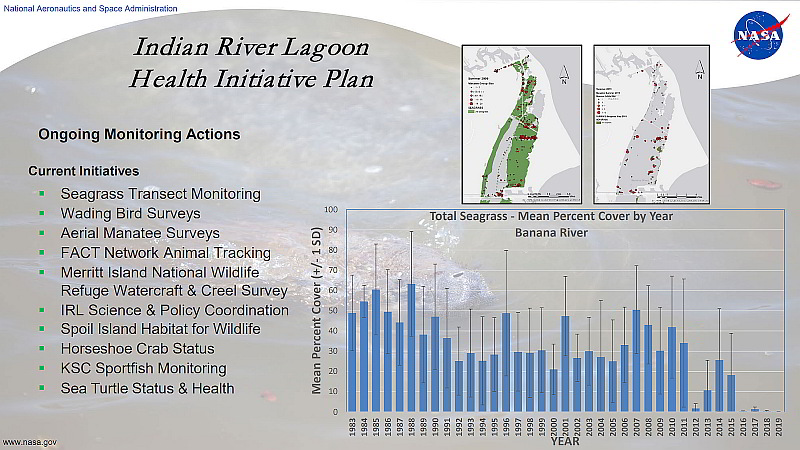

So, this is the meat and potatoes of what our ecological folks do and they are some of the best, again, you know, seagrasses, monitoring since 1983, Doug has a great data set. Looking at seagrass, you can see its on hard times. You can also see how it is related to manatees. No seagrass. Fewer manatee. There’s fewer than that now actually.

We have upped our aerial manatee surveys to twice a month in support of stakeholders, you know, looking forward to what the winter brings for manatee.

Wading bird surveys going on since 1987.

I mentioned the FACT Network. Potentially a creel survey for MINWR.

We’re engaged in IRL Science and policy. Right, we’re here. Doug goes to the STEM Meetings and other groups that we participate in.

You can see the other things below that I have talked about, except for sea turtles.

We don’t know if there is any juvenile turtles in the Banana River or some other areas of Mosquito Lagoon, Indian River. So we might do some sampling just to see what’s there. So that’s some upcoming work.

Proposed restoration actions. We have one funded study that is finishing up in the southwest part of the center looking at a potential regional stormwater pond. There’s no dollars for design or construction. But EAB, Environmental Assurance Branch, is completing that study.

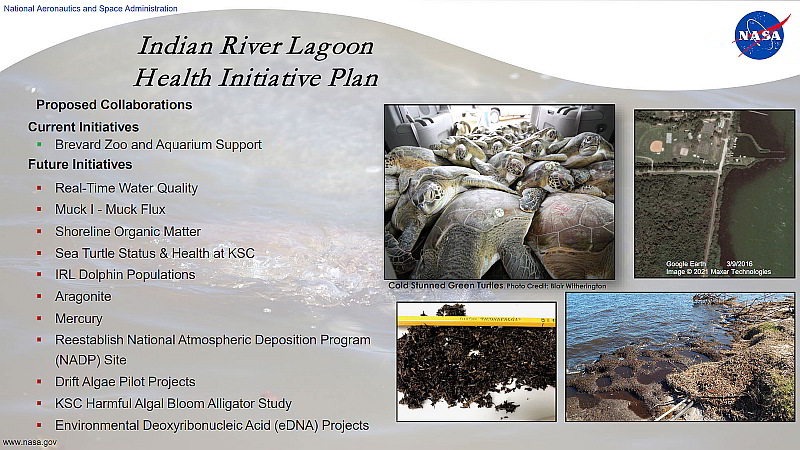

Living shorelines. We have tried before to do work with the zoo for example, Brevard Zoo, on living shorelines. It is a challenge as we collaborate because there are restrictions on the type of dollars and you have to have agreements and these sort of things. And so that has never worked out. But we are doing our own.

You can see out on the road south of KARS park some of the damage to infrastructure, to the road and to the communication lines in there and that’s in the lagoon.

We will be putting in a small revetment, a very short revetment, with a wave break with some soil in between. Hopefully that will attract more sediment so we at least generate some shoreline there. We would rather not do big hard revetments to protect infrastructure in the lagoon. So we are trying to do better than that.

This is a small project that we did on KARS. KARS Park was a big revetment, you can see it from 528. I liken it to … (???).

It can stand out. We did a smaller area, a small wave break with some plantings that has faired very well.

You can see some drift algae, actually that’s culerpa there, and I will talk about that in a minute. That’s a component of the plan as well.

Future dredging. Can we do dredging better to pull nutrients out of the effluent as it goes back into the lagoon.? We are looking at those kind of things.

Shellfish, the Super Clams. We didn’t get any but MINWR got a hold of some, or are getting a hold of some, so they initiated that work. That’s really good stuff, because that’s super important to the restoration of the lagoon and keeping the lagoon healthy.

Septic tanks. I think we have 40 septic tanks on center. They are the 500 gallon variety. So they are not huge. There is an opportunity potentially in the future to take a look at those. Do you put them on the sewer line or do you put some advanced denitrification on the system as you do updates? We will look at that.

Collaborations. I mentioned collaborations. It’s more of a challenge now based on things that have happened in the past where collaborations were held to a pretty high standard with agreements and where a collaborator’s funding comes from. We do pretty good with universities . So that’s good.

Brevard Zoo and Aquarium support. We are not designing the aquarium, I think an article might have said that yesterday, we are adding some input. Eric Reyier is our participant in that. He meets with the zoo and he gives input periodically on some of his expertise with his work with the fishery. So that’s funded.

Future Initiatives. We have talked about an IRLON station up in the north Banana River. You know there is not a lot of data up there in terms of water quality. So that would be something important to make happen.

Muck Flux. We’ve got borrow areas, just like everybody else, we will take a look at that.

Shoreline organic matter again intersecting with shoreline resiliency. We have seen a lot of shoreline loss and it is not just hurricanes, the water is high enough now when we have late September October high water events and an easterly wind we get this black water condition, I call it Blackwater, it works for me, and it really comes from ??? soils and maybe some organic soils that are exposed and so these shoreline projects again are important but what happens is the terrestrial vegetation, and even mangroves that are ripped out of there, get ground up, you know, and a big part of that stays in the lagoon and these these pulpy grind looking remains are tossed back up on the shoreline and so that either accrues as muck or maybe it ends up in the lagoon and eventually some of that is more dissolved organic carbon. Either way is probably not good and so we would like to take a look at that.

Sea turtles. We are going to sample. Potentially we could do some gender studies and the sex determination for them and also genetics. That would be a collaborative action.

Dolphins.

Argonite. Calcium Carbonate. We have all heard about, in this meeting actually, about coastal acidification. So that could be something that we could collaborate in the future on.

Again the collaboration is important. It brings in expertise that we don’t necessarily have and allows us to work with stakeholders and to do more for the lagoon.

Mercury.

NADP site.

Drift algae projects.

You saw the algae before, similar to the organics there. A lot of, not all, but a lot of NASA KSC shoreline is accessible because we have impoundments berms, you know, that you could go around not necessarily with a vacuum truck but something smaller and get some of that material off the shoreline. As we work towards getting this tipping point back to a functional lagoon. I realize it is mostly water but every little bit helps.

HAB study with alligators. We are not studying alligators per se, we had a thirteen year program where we captured alligators, took a bunch of samples, and gave them to researchers. And we did some life history work for alligators at Kennedy Space Center.

Again, that was over a thirteen year period. We’ve got 760 plus or minus samples left from that work that started in 2010 of algae blooms, we started having problems, so we are working to maybe do some work on those samples.

And then EDNA. NASA does not have an EDNA Program again we collaborate with others. The extent of our collaboration thus far has been to take researchers out on a boat and let them collect their samples in places that maybe they can’t get to. And, we’ll see, I don’t think, perhaps there is more to expound on with that. And so we will see what comes in the future with that.

The lagoon plan is available on our national technical report website there is also a lot of other stuff on there, a lot of other reports. You can go in there and search by subject, by author’s name, by title, if you have a title you can pull up that information.

If you have thoughts down the road and you want to share them feel free to email me at NASA.

With that, if you have any current questions or comments I guess we can do that pretty quickly.

(Unintelligible questions)

Related Article

Kennedy Space Center Announces Indian River Lagoon Health Initiative Plan