Tagged: IRL History, Laurilee, Thompson

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 9 months ago by Laurilee Thompson.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

August 8, 2024 at 7:55 pm #2141Laurilee ThompsonParticipant

I’m a fifth-generation Floridian and have spent the majority of my life rooting around the Indian River — enjoying it, observing it, appreciating it, and studying it and all the creatures who call it home, including its most famous resident, the Manatee.

I currently serve on the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program Management Board, Brevard County’s Save Our Indian River Lagoon Citizen Oversight Committee, and NOAA’s South Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

I’m the Chair of the City of Titusville Environmental Commission, Vice-president of the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge’s support group – the Merritt Island Wildlife Association, and a member of the Southeastern Fisheries Association and Bear Warriors United. I served for 20 years on the Brevard County Tourist Development Council, mainly representing eco-tourism.

All three components of the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) system come together in a very special area in northern Brevard County. They are the Indian River, Banana River and Mosquito Lagoon. These estuaries are a mixture of fresh water from natural sources on the land (such as creeks and tributaries) and salt water from the sea. Estuaries are among the most productive ecosystems in the world. In fact, the Indian River was once home to some of Florida’s most bountiful commercial and recreational fisheries where thousands of different animal and plant species cohabitated in one of the world’s most diverse water bodies.

During my lifetime, human development coupled with negligence toward the IRL’s preservation, has manifested into an unprecedented ecosystem collapse. Over my lifespan, I have sadly witnessed its unfortunate demise.

In the 1960’s, rapid escalation of Space Center activity caused great harm to the northern IRL. The connection between the Banana River and the Indian River was severed when NASA built a causeway over Banana Creek and the crawlerway for the Apollo spacecraft was constructed. Massive amounts of Banana River bottom were dredged and dumped over pristine wetlands and waterways to create the Apollo launch pads. More than 100 miles of estuary shorelines were diked in the northern IRL and the salt marshes destroyed in order to build impoundments for mosquito control.

Even more impactful to the IRL was Brevard County’s explosive population growth on the mainland and central and south beaches. Titusville burst from a sleepy fishing and citrus community of 5,000 residents into a small city of 45,000 in just a few years. Brevard County’s other municipalities also experienced extraordinary development. Unprecedented amounts of stormwater and partially treated sewage flowed into the IRL, which was already compromised from the loss of nearly 100% of its saltmarshes and their ability to filter nutrients and pollutants from its waters. The northern and central portions of the IRL system are far from any ocean inlets and very little flushing occurs. What goes into the river stays in the river here.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="887"]

Two-year-old Laurilee on the Titusville Pier’s 4th of July parade float.[/caption]

Two-year-old Laurilee on the Titusville Pier’s 4th of July parade float.[/caption]My early childhood was spent in a house that was right on the shore of the Indian River. My dad built race boats and his first commercial line of fiberglass boats on the ground floor of the building and our family crammed into the small apartment above. My grandfather operated the nearby Titusville Fishing Pier. One day in 1963, I stood with my grandfather on his pier looking south through the pilings of the Titusville Bridge. Five miles away, cranes were working where the NASA Bridge was being built. He told me then that the river was going to die – that it could not endure the new causeways and the pollution that would come as a result of the new people who were moving to Brevard County. My grandfather only had a seventh-grade education. But still he knew that all of the growth and development that was happening would be very bad for the river.

You could catch all kinds of fish off of my grandfather’s pier when I was little — the main prize being spotted sea trout. Black drum, sheepshead, redfish, snook, spots, croakers, whiting, pompano, mangrove snapper, gag grouper, and flounder were commonly caught. Shrimp and blue crabs were netted under lights at night. Folks came from all over the U.S. to stay in Titusville and spend their winters fishing on the pier. Back then, the water in the river was crystal clear. In fact, a stroll down any Indian River dock in the early 1960s was like wandering over a giant aquarium. At times, the water was so clear, you could go all the way out to the end of our pier where it was ten feet deep and see the river bottom. It was common to see schools of mullet swimming under the pier. The same school of mullet could pass by for 20 minutes.

There was a boat basin with a ramp by our house. All kinds of creatures could be found in the small world of our boat basin – sea squirts, barnacles and oysters grew on all of the seawalls and pilings. You could walk along any shoreline of the river and there would be fiddler crabs as far as you could see. Every summer moon jellyfish swarmed in the river. They were so plentiful it seemed like you could walk on them.

My father built a dock for people to tie up their boats. When the wind blew out of the east, big mats of sea grass drifted in. Then the manatees would come to eat the grass. We could sit on the dock and touch their backs with our bare feet. I loved seeing the manatees. They were such gentle creatures, especially when a baby manatee was tagging along.

The manatees only came during the summer. They went south seeking warm water when the weather turned cold. This seasonal migration changed when the two power plants were built in Port St John. Once the manatees realized that warm water came from the power plants, the manatees stopped migrating. After the power plants were built, we occasionally saw manatees around the pier and in our boat basin during winter time too. It was always a joy and a wonder to see manatees, winter or summer.

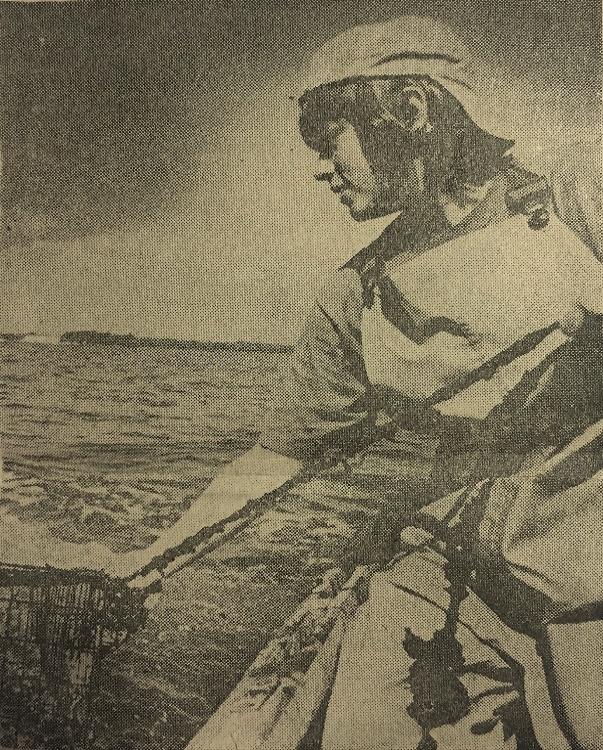

I commercially fished in the IRL from the mid-1960’s through the mid 1970’s, starting out when I was 10 years old pushing a net through the seagrass by Haulover Canal to catch bait shrimp for my grandfather to sell at his pier. I loved seeing all of the things that got captured in my pushnet. There were magical creatures like pipefish and sea horses, crabs and little tiny fish. I also caught a lot of shrimp. I spent several happy summers pushing the net for shrimp, trapping pigfish and splatterpole fishing for spotted sea trout. Every morning I crossed the river by the pier to run the flats heading north. The thing that impressed me most on those trips to Haulover Canal was the never-ending carpet of seagrass that extended the entire length of the river’s eastern shoreline.

I eventually got a bigger boat and motor. My friends helped me build 150 blue crab traps. Back then it didn’t matter where you put a trap in the water – it would always have crabs the next day. I spent a couple of years trapping blue crabs and stone crabs. The next year, I got my first bank loan and I financed enough money to buy 500 yards of gill net, a bigger motor and a bow runner mullet boat. I started spending entire nights out on the lagoon, doing my homework under the dim glow of a 15-watt light bulb.

When the nor’easters of fall sent mullet to the sea to spawn, I ranged further south, looking for roe fish between Melbourne and Sebastian Inlet. It was common to see school after school of mullet moving south – acres and acres of traveling jumping mullet. The giant pods of fish were a frenzy of noise and commotion as pelicans crashed into them and dolphins tore through.

I graduated from high school in 1971. Hoping to temper my crusade to become a full-time fishing fanatic, my parents sent me to Florida Tech where I studied Oceanographic Technology. We reached a compromise and I took a small boat down to Jensen Beach to continue my practice of doing homework at night while my nets soaked in the lagoon. I discovered that the southern end of the Indian River Lagoon is really quite different than it is up by Titusville. There were tropical fish – the same colorful fish you see in salt-water aquariums – and banded coral shrimp and arrow crabs and different kinds of sea grass. For the first time, I caught barracudas in my nets. It was then that I began to understand the magnitude and diversity of this incredible body of water that spans the zone where tropical and temperate climates meet. The sights and sounds that I enjoyed while fishing on the river in my youth are forever ingrained in my being. I cherish those memories as they and pictures are all that is left of the Indian River before it was turned into a toilet.

Soon after leaving college, I started running commercial longline fishing boats out on the ocean. A completely different universe opened for me and the Gulfstream became my new playground. I spent the next decade on the ocean, abandoning life at sea in 1987 to return to Titusville to help out my parents with their seafood restaurant. When I took a kayak trip on the river, I was appalled at what I saw. The once clear waters were murky; the colorful algae and filter feeders on the rocks and pilings replaced by slimy brown smegma. The water clarity was so bad I couldn’t see if any seagrass was present. I couldn’t believe the river had degraded so badly while I was gone – it had only been ten years.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. My grandfather’s prediction was coming to pass. For decades, virtually every wastewater treatment plant along the IRL had been releasing their effluents into the lagoon. I remember seeing solids flowing from Titusville’s sewage outfall, which discharged into the river right next to my dad’s boat plant. Poop regularly washed onto our breakwater.

Additionally, rapidly increasing development was creating significant stormwater pollution into the lagoon with the construction of many ditches and canals that drained into the river. Too many nutrients and fresh water from unnatural sources were flowing into the lagoon. I was so shocked and disappointed at the condition of the lagoon that I buried myself in work at the restaurant. I did not return to the river for nearly a decade.

I cherished seeing manatees from the very first time I saw one swim into my family’s boat basin. It was a special day indeed when I could see a manatee when I was out fishing. In 1997, I started the first guided kayak tour business in Brevard County. That’s when I really fell in love with manatees. To be sitting on the water in a kayak with a manatee rolling nearby that was as big as my boat was as close to heaven as I could get. My clients were over the moon elated to be that close to a manatee and I realized the value of our state’s iconic marine mammal to Florida’s tourism economy.

I also started a birding and wildlife festival in 1997. During its 25-year history, boat and kayak trips on the Indian River were consistently among the most beloved offerings at the festival. Topping the list of favorites were the trips to Blue Spring and a St Johns River Cruise to see manatees. Among the most-often asked questions of servers at my restaurant is this one, “Where is the best place for me to see manatees?” Second only to the Black Point Wildlife Drive, the manatee viewing deck at Haulover Canal is extremely popular with Merritt Island

National Wildlife Refuge guests as are kayak trips where folks might spot manatees. Many of the PR pieces for Florida’s eco-tour businesses I see on TV talk about encountering manatees.

Brevard County led the state in manatee deaths in 2021. 359 manatees perished here, mostly from starvation. Hundreds more manatees died from starvation in 2022. This is a man-made disaster, the result of decades of too many nutrients and other pollutants going into the Indian River Lagoon. Resulting algae blooms shielded seagrasses from life-giving sunlight and they died, releasing even more nutrients into the water to fuel even more algae blooms and kill even more seagrass. 95 percent of the seagrass coverage in the northern Indian River has evaporated leaving nothing for the manatees to eat.

This emaciated manatee was rescued from DeSoto Canal in Satellite Beach on February 8, 2021. It succumbed to starvation the following day. Manatees cannot scream out loud, although this one surely seems to be trying. If they could shriek, our Indian River would reverberate with their cries. It takes a long time for a manatee to starve to death — months or even years. With little body fat available, first their muscular system is consumed. Once that is gone, their organs melt. It is a slow painful death. This manatee chose to go to DeSoto Canal in Satellite Beach to share with the world its death throes. It could not scream, yet it still managed to broadcast its anguish to the circus-like crowd of daily onlookers. State officials removed it from the water and put it into a city maintenance truck to eliminate it from view.

How long can we stand silent and allow this sad annihilation to continue? It tears my guts up to helplessly watch the trailers with dead manatees passing through my town. Aren’t there government agencies that are supposed to prevent atrocities like this from happening?

The Indian River is sick. 95 percent of seagrass coverage in the northern IRL system has disappeared and the river bottom is a desert. It’s rare today for folks to catch anything but hardhead and gafftop sail catfish off of the Titusville Pier. Shrimping and crabbing efforts yield pathetic results compared to the days when we had seagrass in the northern IRL. The great schools of mullet of the past are gone and numbers of predator fish and birds that depended on mullet diminished. In the “Redfish Capital of the World,” IRL redfish were recently designated catch and release only. Production by offshore shrimpers of finfish that use IRL seagrass beds as a nursery plummeted. These include flounder, whiting, croakers and spots.

I ended the Space Coast Birding and Wildlife Festival. Due to the deplorable condition of the IRL with its hundreds of starved manatees, I could not in good conscience continue to market Brevard County as a stellar place for people to come and see wildlife. I had 25 years of my life and hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in that event. It broke my heart to end it.

Forty years ago, my parents opened a seafood restaurant in Titusville that featured locally caught seafood, much of which came from the Indian River. We are still there but our menu has changed. We no longer serve IRL product because we can’t get it. On occasions when I can get enough mullet to offer, it mostly comes from Florida’s west coast.

It wasn’t that long ago when the Indian River ruled as Florida’s most productive estuary. It supported hundreds of fishermen and their families. Today, its once vibrant commercial and recreational industries, including eco-tourism, have been decimated. Very few individuals try to eke out a living from its polluted waters.

“Rainy day” releases into the IRL of partially treated sewage from wastewater treatment facilities occur with ever increasing frequency as aging infrastructure allows groundwater to enter sewer pipes and exceed capacity at sewage treatment plants. Overwhelmed lift stations fail and sewage flows from manholes down the streets of our neighborhoods. Not only is this disgusting, it’s a human health hazard. Aren’t government agencies supposed to protect the public from outrageous events like these?

In 1987 the Florida legislature passed the Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan (SWIM) Act. The SWIM Act required the state’s five water management districts to develop plans to protect and restore certain priority water bodies within the state. The IRL was one of the priority water bodies that was identified.

At the federal level in the same year, Congress passed the Water Quality Act of 1987, amending the Clean Water Act of 1972. This amendment created the National Estuary Program (NEP) with the purpose of protecting and restoring estuaries of national significance.

To complement state restoration efforts, the IRL was nominated for inclusion in the NEP in 1990 and, following a review by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (IRLNEP) was initiated in 1991.

Also in 1990, the Florida Legislature passed the Indian River Lagoon System and Basin Act requiring sewer plants to stop discharging into the estuary by 1996. The act aimed to protect the lagoon from wastewater treatment plant discharges. It also included investigation of feasibility of reuse water, and centralization of wastewater collection and treatment facilities. So many laws passed and yet the IRL is more polluted than ever!

From a 2007 St Johns River Water Management District document entitled Indian River Lagoon: An Introduction to a National Treasure, I quote,

“The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population of the IRL region at 1.54 million with growth anticipated to continue. The challenges of dealing with the environmental impacts of a growing population and resulting changes in the landscape of the region will require diligent and effective management to protect, preserve and restore the resources of the IRL for future generations. Through the management initiatives and environmental enhancement objectives implemented by the IRL Program in collaboration with local, regional, state, federal and private efforts, these challenges can be met, ensuring the continued health and productivity of the IRL.”

More than 1.86 million people are now living in the IRL region and there is no indication that the population growth will slow down.

This organizational tree displays the U.S. Government hierarchy over the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program:

United States Government

Executive Branch

Environmental Protection Agency

EPA Office of Water

EPA Office of Wetlands Oceans and Watersheds

Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program

These agencies are supposed to be helping the IRL survive ecologically. Some of these agencies have been around since the 1980’s. I ask: What on earth have they been doing all of this time? They have failed in their mission and responsibility to ensure that the Indian River is cleaned up and its destruction ended.

I have been a volunteer water tester for the Marine Resources Council for the past five years. One of my testing sites is the Beacon 42 Boat Ramp, which is on the western shore of Mosquito Lagoon (ML) a mile north of Haulover Canal. I have visited that site every week since May 2018. When I first started testing at Beacon 42, there were crab trap buoys in the lagoon running north as far as I could see. The seagrass was so thick and lush it bent over at the water’s surface. Fishermen could not efficiently operate small trolling motors without winding so much grass around their propellers that their motors shut down.

In February 2019 huge wads of seagrass washed up along the shoreline. For two years the seagrass never came back. The crabbers pulled their traps and moved out. It was rare to see a manatee at the Haulover Canal Manatee Viewing Deck. I asked every fisherman I encountered whether they were seeing seagrass anywhere they had been. The answer was always no. The last large algae bloom faded in January of 2021 and the summer of 2021 passed without a major bloom. Slowly the seagrass in the southern ML started to recover.

With the help of friends, I was able to harvest small amounts of floating seagrass pieces with rhizomes (roots) to send to a seagrass farmer to grow in tanks for seagrass planting restoration projects. The yield for 2021 was 120 pounds. The seagrass has grown back like gangbusters during the summer of 2022. Thus far this year I’ve sent more than 1500 pounds of seagrass with rhizomes to the seagrass farmer.

Visitors have been ecstatic this summer to occasionally see large numbers of manatees at the Haulover Canal viewing deck. Of course, in years gone by this was a common sight. During the week of July 11, NASA scientists counted 858 manatees in the southern ML. I have observed many manatees in ML mating and frolicking and acting normal. I guess it makes a difference in your behavior when you have plenty to eat.

Three weeks ago, a crabber put out crab traps at Beacon 42. Those crab traps wouldn’t still be there if they weren’t producing crabs. Phenomenal recovery of seagrasses in the southern ML shows how effectively this damaged system can recover without stormwater and sewage pollution going into it. The southern Mosquito Lagoon is bordered by the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge on the west and Canaveral National Seashore on the east. Here is the most important fact: NO stormwater ponds or wastewater treatment facilities discharge into its waters.

We live in a world of ever-changing baselines. What seems ordinary to new generations is unacceptable to those who came before. I will never see the Indian River the same way that my grandfather saw it. What’s abhorrent to me is normal to my grandchildren. They have never seen a shoreline covered with fiddler crabs or a water column filled with graceful moon jellies. They’ve never been able to pull an oyster or clam from out of our river and safely eat it on the spot. Just because polluted water seems normal to newcomers doesn’t make it OK!

One way to measure the character of a community is to look at what it protects — we safeguard what we value. Generations of my family and many others have depended on a healthy Indian River to make our living. The economic worth of unpolluted water through the creation of jobs in the fishing, tourism, recreation and other industries is well documented. It has been shown time and again that property values increase in direct proportion to their proximity to clean water bodies.

Fossil remains of manatee ancestors show they have inhabited Florida for about 45 million years. They are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and protected under federal law by the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, which makes it illegal to harass, hunt, capture or kill them. They are also protected by the Florida Manatee Sanctuary Act of 1978.

Not only is it inexcusable that we have been discharging sewage and other nutrients into their home for so long that their food has disappeared and they are tragically starving to death, this is an unlawful violation of the ESA.

Obviously, measures that were put in place decades ago to address nutrient loading in the IRL are insufficient to keep pace with development. Better policies for pollution control should be created and state agencies should be required to set higher goals for nutrient reduction immediately.

We will know success when once again the Indian River has enough seagrass to support thriving commercial and recreational fishing industries and manatees can flourish. When that happens, everyone else who depends on the Indian River for a living will prosper. People will be able to recreate without fear of touching the water or eating the fish and the specter of large-scale algae blooms and canals full of dead animals will just be a bad memory.

It’s embarrassing for Florida to allow this to happen to our state’s beloved marine mammal. Based on the global media that has captured the attention of humanity, clearly it is time for Florida to fix the problems that are killing these magnificent gentle creatures that have done nothing to deserve this fate.

The continued degradation of our water quality is a threat to Florida’s claim to be the “Fishing Capital of the World” as the disgusting condition of our waters has collapsed our both our commercial and recreational fisheries.

For no other reason than just to uphold our tourism economy, Florida must address the sewage and nutrients that are ruining our waterways.

It’s our duty to leave a healthy Indian River Lagoon as a legacy for future generations to enjoy.

The world is watching to see what we will do.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.